Van bassengwerker tot havenarbeider (Antwerpen)

1965 00:47:49 b&wIn 1965 more than 13,000 labourers set to work every day in the port of Antwerp and even then, every day there was a shortage of workers. “The Antwerp docker is the quickest in the world,” we hear in this creative documentary, “though they never had any specific training for their job—except for the markers.” The surplus of jobs available drew all sorts of people to the port ‘though most of them had previously failed in a different trade,” we hear the commentator declare. The voice-over sharply explains the goings-on in the port in the mid-1960s, while the first images of his documentary show us stevedores and port labourers who present themselves in the large recruitment hall, hoping to find a day’s job.

In ‘Van bassengwerker tot havenarbeider (Antwerpen)’ (“About Stevedores and Port Labourers (Antwerp)”) we are informed that port labour was a non-stop business, which was therefore divided in eight-hour shifts that included a thirty minute break. Each team comprised between eight and seventeen men that were divided in various categories: down-men and up-men, holemen, samplers, gaugers, weighers, markers, etc. Each team was headed by a foreman and a “seefbaas”, who supervised the work on the ship and in the port.

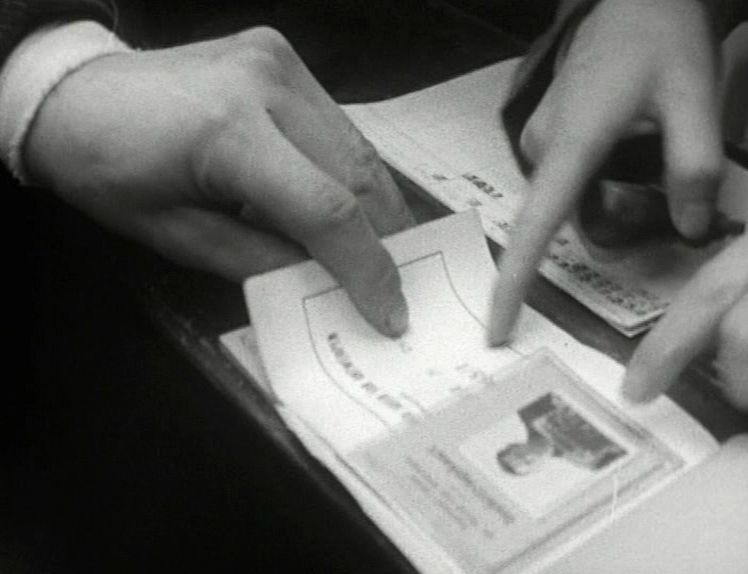

There were no weekly or monthly contracts for these hard, unskilled jobs. The workers were employed for a single day with a day’s contract, which meant they had to present themselves every day—which was not the case for senior workers or executive staff. Because the work was paid little or even poorly, a compensation fund was created in order that the workers should have an income they could live off.

In the documentary we see stevedores loading and unloading ships that carry a variety of cargo: sand, oil, packages, sacks, crates and even cars. During their break we hear them talk about their pay, which consisted of a fixed wage and extras, depending on the number of goods moved. A voice-over then continues to explain the complex remuneration system, including all numbers and percentages involved. A little later we see how the workers are paid daily in the room near the exit and we hear the bosses talk about their workers’ position.

Cornelis never judges during this entire film—he merely shows the workers and explains their precarious situation. This implicit comment turns the film into a strong historical pamphlet, a silent social critique.

Directed by Cornelis, Jef